Feeling fat vs. being fat: Who gets to claim fatness?

The complexity of size identity. Plus, an unexpected weight check in Panama.

Most of us, regardless of our size or level of body acceptance, don’t want to be fat, let alone call ourselves fat.

But what does it really mean to be fat? And who gets to claim that identity?

Thanks to diet culture, most of us have believed we were fat at some point in our lives, whether or not we actually were. We’ve felt the body dissatisfaction—maybe even lived with it so deeply that it felt like truth. But here’s what many of us don’t realize: there’s a difference between feeling fat and being fat. The latter doesn’t just shape our self-perception; it dictates how the world treats us.

And I’ll be the first to admit, even though I often write about body acceptance, weight gain, and weight stigma, I hadn’t given this distinction much thought until recently.

Fatness and the Ozempic effect

In December, I published a piece about my experience "going fat" in the time of Ozempic. It quickly became my most popular post, and is still racking up likes and comments months later.

One of the most interesting comments came from Amanda Martinez Beck, who had written herself about using Ozempic for diabetes. She lost weight on the meds but found it didn’t improve how she felt about her body.

Her story is one I recommend reading. It raises an important question: What happens when we lose weight, but not enough to change how the world perceives us—or how we perceive ourselves?

Before we go further, I want to be clear that I’m not anti-Ozempic. I believe people should have body autonomy. But after years of losing and regaining the same 10, 15, 20 pounds, sometimes with prescription meds, I know this path well enough to recognize it’s not for me. And even though I’d qualify for GLP-1s based on BMI alone, I’m still relatively healthy. (I had my first high cholesterol reading last year at 49, but for now, I’m managing it without medication since it’s a known side effect of perimenopause.)

For me, the risks of GLP-1s for weight loss still outweigh the benefits. More importantly, I believe bodies exist in a range of sizes and shapes, and I have no interest in modeling intentional weight loss to reach an unrealistic ideal.

When Martinez Beck commented on my piece, she praised my perspective but raised a concern about the headline. As someone who is “newly fat,” on the lower end of fat, and still benefiting from thin privilege in many ways, I wanted to know if I had been insensitive, so I reached out.

Her response? The title was attention-grabbing, but did I actually identify as fat? She stopped short of asking whether I was one of those people who call themselves fat but really aren’t or, worse, was simply using the word fat for clicks.

She included links to content she had written to help people determine where they fall on the fatness spectrum. She also pointed out that many people claim fatness without ever experiencing the realities that come with it—stigma, lack of accommodations, and discrimination.

My first thought? Did you not see my picture? Did I not look fat enough?

And maybe that’s the point.

When fat is more than a feeling

We don’t always see ourselves clearly.

There are plenty of people in not-fat bodies who feel fat all the time.

We’ve all have that one person who is skinny—or at least skinnier than us—who insists she’s fat. She critiques her body constantly, never considering how her words land for the people around her.

And, yes, dysmorphia is real. We often don’t perceive our bodies as they actually are. I’ve experienced this most of my life. From high school until two years ago, I was locked in battle with mine, convinced I was bigger than I actually was. My kids look at pictures of me from high school and wonder how I ever thought I was fat.

I used to feel fat in my size-12 body—but I never worried about whether I’d fit in a chair or on a massage table, or find clothes in my size. Since ditching diets, these are some of my everyday concerns.

But why does the distinction matter? Why do we need to categorize fatness?

Martinez Beck’s argument was that many people claim fatness without ever experiencing what comes with it—stigma, lack of accommodations, limited clothing options, and outright discrimination. And the further you are on the fat spectrum, the harsher these realities become.

Now, as a size 16-18, still on the lower end of fat, I still have days when I feel fat.

The difference? By all measures, flawed as they may be, I am.

But here’s something interesting. Some days, I don’t feel fat at all. My best days are the ones when I don’t think about my body—positive or negative. I’m just living, not stressing over a number on a scale or how I look or feel in my own skin.

A weight limit and a reality check in Panama

I stopped weighing myself three years ago when I quit Olympic weightlifting and no longer had to “make weight” when I competed a few times a year. I still wouldn’t know my number, except during Christmas vacation, my family and I chartered a flight from Panama City, Panama, to the San Blas Islands, that had a weight limit for passengers.

Visiting these pristine Caribbean islands wasn’t part of our original plan, and we didn’t think we’d find a flight last minute for a reasonable price. So when my husband found a pilot, he was thrilled—until the final request came in:

"We need everyone’s weights."

I knew the girls’ weights from recent doctor visits, but of course, I had no idea about mine. I took my best guess and then immediately started fretting.

My husband passed the numbers along, and the response came back: It’s gonna be close. Don’t pack anything extra.

For a moment, I joked with my husband that we should hit the hotel sauna and cut some water weight, a technique I’d perfected during my weightlifting days. But I quickly realized the flaw in that plan.

Between us, we could easily drop 5–10 pounds of water before we left, but what about the return trip? Being in water can actually make you retain it, especially if you’re already dehydrated. Even if we avoided drinking anything the entire trip (a terrible idea on its own), we might still end up heavier than when we boarded.

So I decided to just deal with it. We’d either make weight or we wouldn’t. And if we didn’t, I’d stay behind. But I really wanted to go.

Because these islands are so remote—most of them unpopulated—and tightly controlled, they have remained unspoiled. Just off the coast of Panama and Colombia, they are an independent territory, governed by the indigenous Guna people, who live and work on the island largely as they have for decades, primarily subsisting on seafood and coconuts. There is no wifi, credit cards aren’t accepted, and electricity is powered by a generator. Even more remarkable, this is one of the few matriarchal and matrilineal societies in the world.

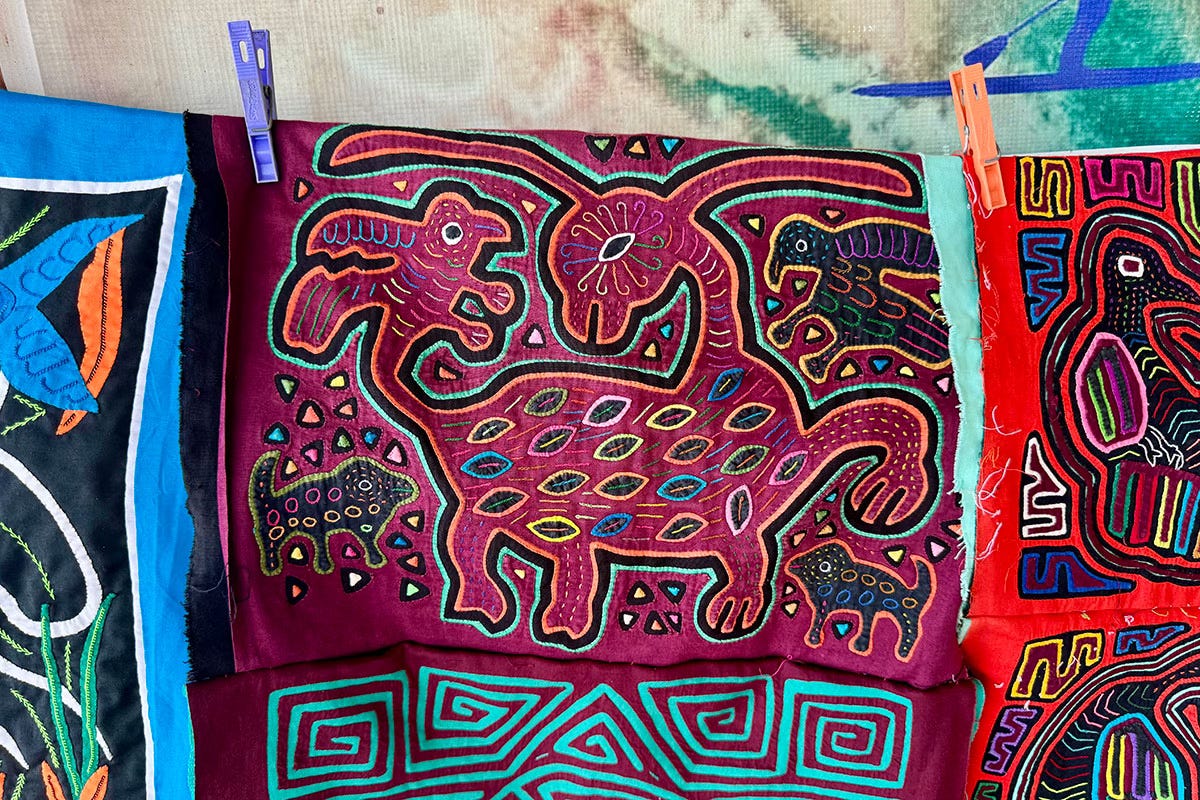

The women are the breadwinners here, crafting molas, these intricately quilted, hand-stitched squares they wear and sell to tourists. Some are sewn into clothing, purses and even shoes, while others are hung as art. A few are even displayed in the Smithsonian. Before the arrival of fabric, Guna women painted these designs directly onto their bodies, believing they would ward off evil spirits.

Reading about these women and their society, I really wanted to have this experience. And if it wasn’t by plane, it wouldn’t have been possible.

But when we arrived at the airport the next day, a whole new wave of concerns hit me.

At my size now, flying comes with anxiety about whether I’ll fit comfortably. Yes, I can always get into the seat, but it’s tighter than it used to be. I feel the armrests pressing against my flesh. The seatbelt has less slack. So far, I haven’t needed an extender, but the fear is always there.

When I saw the tiny six-seater, my first thought was holy crap! Even if I make weight, am I even going to fit in this thing?

After getting settled in the hangar and chatting with the charter owner, just for a second thinking maybe we wouldn’t even have to get weighed, we were lined up one by one. I stepped on the scale last, cursing that I needed to be fully clothed even with the ungodly number of strangers gathered around for the big reveal. The number flashed across the screen for a second. I almost didn’t believe it was real.

It was a good 15 pounds higher than I had estimated, and yet somehow we were still cleared to go. And thankfully the seats were just fine.

San Blas was everything I’d imagined, but days later, questions lingered.

Numbers and diet thoughts

There was a time knowing my number would have sent me into a spiral. For years, I obsessed over the scale, convinced less weight was the key to happiness.

And for a few days after San Blas, the old diet thoughts crept in:

Could I lose just enough weight, without getting sucked back into food obsession, to avoid situations like this? Could I diet just enough to make my body fit more comfortably in this world? Even being just one size smaller would open up more options for me.

I looped on these thoughts for days, each time reaching the same conclusion: The only way for me to reach body peace was to keep letting go of the eating rules and body hangups that had plagued me most of my life.

The problem with calling ourselves fat

Whether or not we realize it, calling ourselves fat—especially when we aren’t—reinforces weight stigma. Whether we say it aloud or just to ourselves, even in a fleeting moment of self-criticism, it upholds the thin ideal. It creates a sense of otherness, distancing us from bodies that don’t meet beauty standards, including potentially our own.

And when a thin or smaller-bodied person calls themselves fat in front of others—especially people who are larger—it sends an implicit message: If they think they’re fat, what do they think about me?

Often people use feeling fat as a kind of apology or excuse for not upholding the ideal. I ate too much. I feel so fat. It’s often a bid for reassurance—because when we say it out loud, we expect a response like, No, you’re not!

But people in fat bodies don’t get that same comfort.

Fat as a neutral descriptor

When I asked myself whether I was really fat or just feeling fat, I had to think.

Yes, I’m on the lower end of the fat spectrum, somewhere between a small fat to mid-fat, depending on whose reference you use.

Yes, I still benefit from privileges that people in larger bodies don’t. I fit in most chairs and airline seats (but not always comfortably), I don’t need a seatbelt extender, and I can still find clothes that fit—though sometimes only online. I’ve never experienced outward discrimination from a doctor. No one has ever stopped me at the grocery store and commented on my food choices.

But I do see myself as fat.

Over the last couple of years, I’ve worked to create a body-positive, size-inclusive home, a place where we can talk openly about these things. Body neutrality, fat phobia, and size inclusivity are regular dinner table topics.

In our house, "fat" isn’t a bad word. My children, now teens and young adults, know bodies come in all shapes and sizes, and that weight exists on a spectrum.

I identify as fat—along with strong, smart, and sexy.

For me, using "fat" is a way to destigmatize it.

I think it’s important for all of us to understand the spectrum of fatness so we recognize that the larger a person is, the more discrimination they face and the more barriers they encounter in daily life.

It’s a reality those of us in smaller bodies often don’t fully grasp.

Straddling these two worlds has shown me how much privilege I had but didn’t recognize. It’s also shown me just how unaccommodating and hostile the world can be to those in larger bodies. It’s made me a kinder, more empathetic person—but it’s also a reminder I still have further to go.

I wish I had understood all of this back when I wasn’t fat but thought I was. And I’m still figuring it out.

I’d love to hear your thoughts. How do you define fatness? Have you ever had a moment that shifted how you see your body? How has your understanding of body size, privilege, and identity evolved over time?

P.S. – If this post resonated with you, would you consider restacking it and sharing it with your audience?

It helps more people find this conversation and supports my ability to keep writing about body acceptance, fat identity, and diet culture. 💙

This is such a powerful piece. I will be awhile unpacking everything this brought up for me. You call me to turn and look inward, to examine my biases and judgments and all I can say is that I’m sorry this even needs to be pointed out. Thank you Kristi.

As

Someone who has never faced this kind of discrimination I need to have my eyes opened about everything you said. When we know better we do better.

Those islands look absolutely beautiful! Wow. So glad you were able to experience them!

Another great essay, and one that has me thinking about Ozempic again because I just went to my new doctor here in Virginia. We did all my bloodwork and I told her I was worried about diabetes and my weight. My bloodwork came back and although I'm just on the borderline between normal and prediabetes, my Lipid panel was all high - high cholesterol, high trigylcerides, etc. My doctor asked me if I'd consider using the injections for weight loss and I said I had...but whenever I do research on it, I just worry about the side effects. Granted, I'm on a LOT of meds already and who knows how Ozempic or a similar one would react to my meds? There are days where, like you, I feel great in my body and am not worried about my weight. But then I see my health might be improved by losing weight - because that's what happened in the past. I had high cholesterol, trigylcerides, etc., and I lost weight, and the numbers all went down. So now I'm just so, so confused as to what to do. I don't eat badly - but I don't get enough exercise because of my chronic illnesses, so losing weight just feels impossible.