First diet culture came for fat. Now it’s coming for muscle.

Why Serena Williams’ GLP-1 weight-loss endorsement sets a dangerous precedent for women’s bodies.

Tennis legend Serena Williams is promoting GLP-1s through the telehealth provider Ro, and at last, finally, FINALLY, the internet is not okay with it. Even as an advocate for body acceptance, I’ll admit I didn’t immediately understand why this particular pairing drew such backlash, because she’s certainly not the first celebrity to admit to GLP-1 use for weight loss.

But the more I thought about it, the more I realized this one is different, and more alarming, than the others.

‘Her body, her choice,’ and the bigger problem

Most of the backlash I’ve seen around Williams’ GLP-1 endorsement centers around the idea that she doesn’t “need” to lose weight. Others have been critical of her motives, pointing out that her husband is an investor and sits on the board of Ro.

The majority of comments I’ve seen defending her decision go something along the lines of “her body, her choice,” and I totally get this. At the end of the day, it is her personal choice to take a GLP-1 to feel better in her body. I support this for her and for every woman who makes this choice, because there is an insane amount of pressure for women to conform to body standards.

But none of these points gets to the real issue. What makes this different is that Williams isn’t just another celebrity fending off speculation about her body. She’s our first major athlete, albeit retired, to promote GLP-1s for weight loss. And that changes everything.

As the face of Ro, she isn’t just endorsing a drug with serious side effects. She also isn’t just losing weight for herself. She’s selling weight loss. And that’s what makes this deal so dangerous: the message, loud and clear, is thinness above all else.

From ‘love who you are’ to not enough

Less than five months ago, Williams told Women’s Health:

“I've always been someone that felt like you have to just love who you are, and I've always felt that way.”

But in her new exclusive interview with the magazine to announce her partnership with Ro, she explained her reasons for taking GLP-1s:

“I am a very good use case of how you can do everything—eat healthy, work out to the point of even playing a professional sport and getting to the finals of Wimbledon and U.S. Opens—and still not be able to lose weight.”

This is a woman who won the Australian Open while pregnant. She’s arguably the most decorated female athlete in history, with 23 Grand Slam singles titles and four Olympic gold medals. She’s had two daughters, nearly lost her life giving birth the first time, and still, the message she’s sending is that even her body isn’t good enough.

That’s what why this deal feels like such a turning point.

When muscles were proof of progress

Until now, no matter how much we’ve celebrated thinness, we’ve also celebrated the stronger, more muscular bodies of our female athletes. Because our female athletes weren’t just winning medals, they were shifting culture. They were proof that muscles and strength could be beautiful.

These bodies became symbols of progress: that women could be strong, competitive, and still feminine. They showed us that women didn’t have to shrink themselves to be accepted, that their accomplishments could be just as valued as men’s.

Williams herself embodied that shift. She was unapologetically muscular in a sport that once prized willowy frames. She faced criticism for her body throughout her career, yet redefined what excellence and femininity could look like.

And that’s why William’s deal with Ro feels like such a step backward. When even Serena Williams, the athlete who once proved muscles could be beautiful, is promoting a weight-loss drug, it risks erasing decades of progress, hers and ours.

And I fear this is just the tipping point in a larger shift that’s been building ever since Ozempic exploded onto the scene.

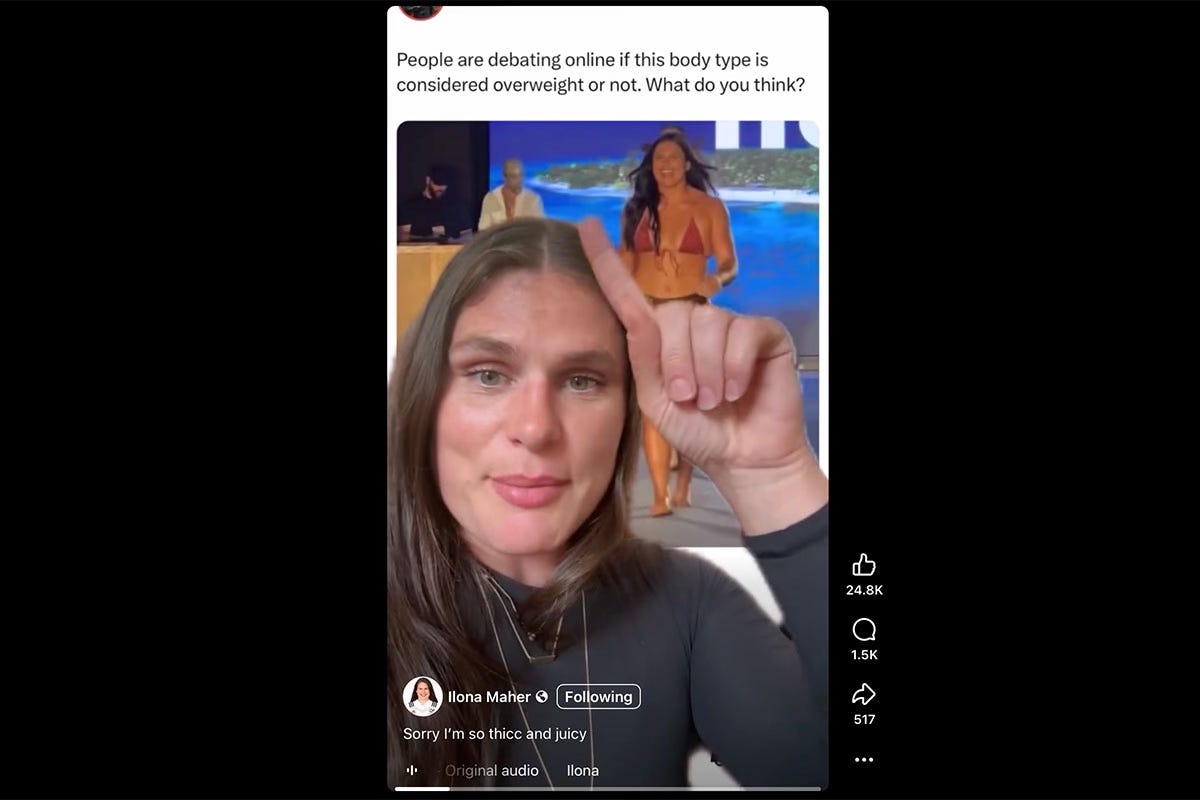

We saw it a few months ago when rugby Olympian Illona Maher walked the Sports Illustrated swimsuit catwalk, and people were asking whether her body type was “overweight or not.” The real question wasn’t fat or muscle, as if our bodies can be only one or the other, but whether it’s acceptable to inhabit this more athletic body type at all.

Since the rise of GLP-1 use for weight loss, there’s been a disturbing shift in how we view muscle in women, as if it’s optional, or even undesirable.

Why muscle matters

Having muscle isn’t just about aesthetics, it’s the foundation of women’s health. Muscle loss undermines metabolism, weakens bones, depletes nutrition, and increases long-term risks—from frailty and falls to chronic disease and loss of independence. Studies show that postmenopausal women with sarcopenia, or age-related muscle loss and strength, are more than three times as likely to develop osteoporosis than those without it. For women, losing muscle is losing health itself.

And while all weight loss includes some muscle loss, research shows up to 40% of the total weight lost from GLP-1s comes from lean mass. It’s a sobering number, yet the pressure to be thin is so overwhelming that women are doing whatever it takes to get small because it’s less okay to take up space now than it was even three years ago.

A culture sliding backwards

We see this most clearly in the consumer sphere. Over the last few years, many retailers and designers have reversed course on offering plus-sizes, both in manufacturing and availability in stores. Just this week, Southwest Airlines announced it would begin charging larger passengers for second seats, ending its previous policy. It was the last major airline with the more lenient policy.

Meanwhile, our social feeds are flooded with thin white influencers promoting the various incarnations of GLP-1s or supplements to blunt the drugs’ harsh side effects. A medication designed to treat diabetes is now marketed as an expectation: we should all be on one.

And from this vantage point, you might say good on Williams for getting out there and grabbing a piece of the pie.

She’s had no shortage of big advertising deals over the years—Nike, Gatorade, Gucci—but her Ro partnership is different. While the financial terms of her multi-year ambassadorship weren’t disclosed, she stands to make a significant amount from it, especially since her husband, Reddit co-founder Alexis Ohanian, is an investor who serves on Ro’s board. But this isn’t just about Williams.

When one of the strongest, most successful athletes in the world feels the need to shrink herself, muscles and all, what message does it send the rest of us?

Younger women will see this as proof they must do everything possible to be thin, even at the expense of muscle. Older women will take it as yet another reminder that their bodies are not supposed to change, and they must do everything in their power to resist the inevitable shift that comes with aging.

The result is the same: a culture that normalizes disordered eating, fuels eating disorders, and risks raising a generation of women who will sacrifice strength for thinness, endangering bone density, long-term health, and even their lives.

And that may be the most dangerous message of all: strength is expendable, thinness is essential.

💬 I’d love to hear from you.

What do you think of Williams’ GLP-1 endorsement? Do you see it purely as personal choice or as part of a bigger cultural message about women’s bodies? Have your views on strength and health shifted in the GLP-1 era?

I’m a pharmacist and I worry that in ten years this is going to be another fen-phen. The heart is a muscle, too. Just as with any medicine, some people do really need it, AND the use to conform to thinness is disturbing to see for all the reasons you laid out. Thank you for this.

Thank you for writing this! I think it’s such an important conversation to have. As a fitness professional, it’s shocking how little people understand about the way these drugs work yet are desperate to get their hands on them. There’s a lot of misinformation and confusion around the role muscle plays in our overall health and well being- it’s not simply about being ripped. Of course everyone should make their own decisions regarding the trade offs, but so much reality is being suffocated by gatekeepers motivated by financial gain.😣