When recovery isn't a straight line: What 'SLIP' teaches us about healing

Reflections on Mallary Tenore Tarpley’s deeply reported eating disorder memoir, and what it reveals about the realities of recovery.

When it comes to eating disorders, those of us with firsthand experience, whether as caregivers or sufferers, tend to think in extremes: you’re either in the grips of illness or fully recovered. There’s little recognition of the messy, often prolonged middle ground.

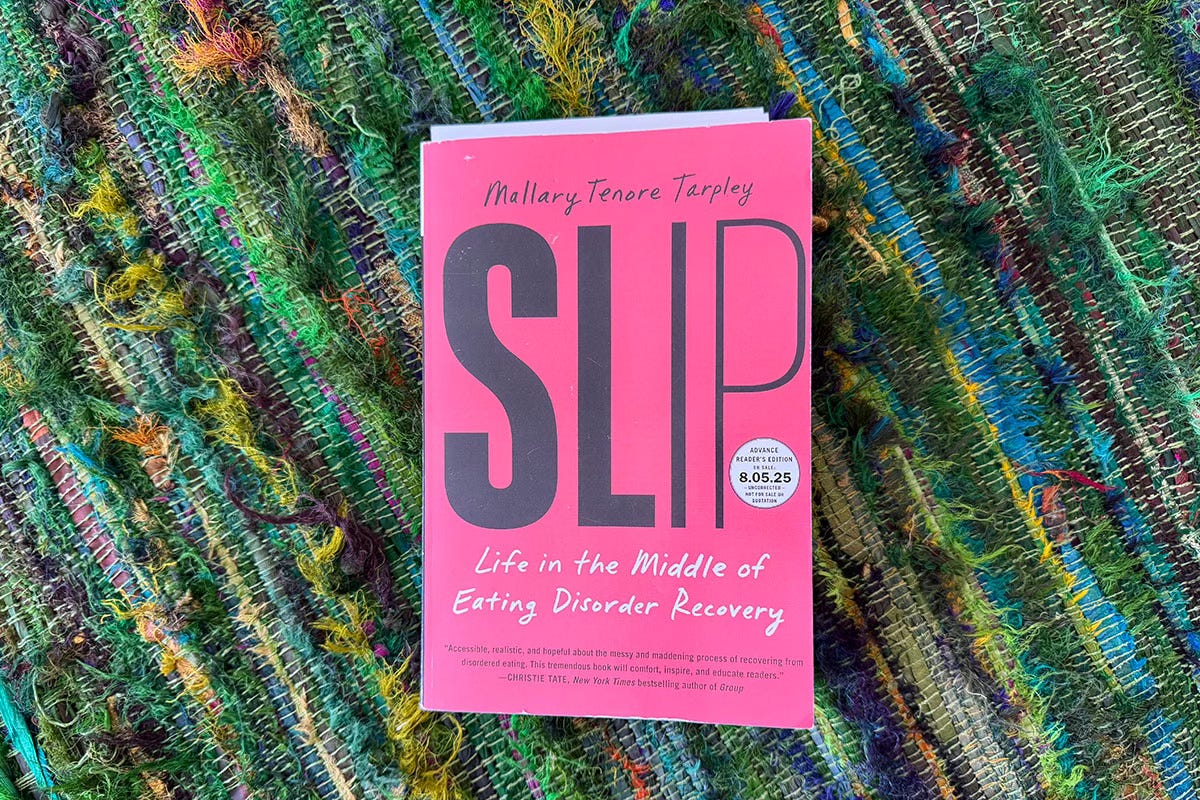

Yet it’s precisely this less-defined space where Mallary Tenore Tarpley centers her well-researched, wrenching memoir, “SLIP: Life in the Middle of Eating Disorder Recovery,” which publishes Aug. 5, and that focus is entirely intentional.

The truth is, the vast majority of those with eating disorders are living somewhere in this middle place.

What does recovery really mean?

Part of the ambiguity stems from semantics; there’s no universal definition of eating disorder recovery among clinicians. Some define it as the absence of physical and behavioral symptoms. Others add a third, psychological criterion: when obsessive thoughts about food or body image subside and self-worth is no longer tied to weight, shape, or control over food.

By this more stringent criteria, recovery becomes harder to reach, not just for most people with eating disorders, but arguably for most women in the Western world.

Rather than trying to define it, Tarpley’s “SLIP” invites us into the lived experience of recovery, what she calls the “middle place,” in hopes of dismantling the stigma that surrounds those who don’t identify as “fully recovered.”

“The phrase ‘in recovery’ has become acceptable when speaking of alcoholism, drug addiction, or perfectionism. But if you say you’re ‘recovering’ from an eating disorder over a prolonged period, there can be an assumption you’re somehow not trying hard enough or you’re undermining yourself. Many of us in the middle place are trying hard as we can, though, all the while knowing we remain at risk.”

A memoir told in two voices

Tarpley traces her journey with anorexia from childhood into adulthood, where she is now a wife and mother navigating her own recovery while striving to protect her two young children from both her past experience and diet culture’s pervasive grip. Each chapter is divided into halves: one part a narrative from her younger self’s perspective, the other a present-day reflection grounded in reporting and research.

The book opens with the confluence of circumstances that led to Tarpley’s eating disorder: her mother’s extended battle with breast cancer and death when Tarpley was just 11, an article in Seventeen magazine that introduced her to eating disorders, a public school weigh-in, and a seventh-grade health class that labeled foods as either “good” or “bad,” after which she began restricting.

She writes:

“I liked the idea of staying small; it made me think about staying the same size I was when Mom was still alive. Maybe if I stayed small, I could feel closer to her.”

Tarpley’s restriction wasn’t rooted in a desire to meet beauty standards, but a way to process loss and find control amid grief and change.

A broader look at treatment

Her experience underscores a central theme of the book: eating disorders often defy assumptions. Tarpley challenges the widespread belief that they always stem from a desire to be thin, or that sufferers are exclusively young, white, underweight, female, or affluent.

To broaden the narrative, she interviews researchers and clinicians, including those who once treated her, and dozens of other individuals living with eating disorders. She even returns to the treatment facilities she once attended, layering others’ insights with her own in a bid to better understand and reframe her own experience.

She examines the continued barriers to treatment, from systemic gaps in care to the difficulty of getting people into treatment in the first place. Most notably, she calls out the persistent weight bias within the medical community, becoming a powerful advocate for those who are often overlooked or misdiagnosed.

She writes:

“Of the roughly 700 people whom I surveyed for this book, 51 percent said they’ve faced weight discrimination while receiving eating-disorder treatment and/or medical care. Some describe instances in which their doctors didn’t think they were suffering from an eating disorder because of their body size. Others said they were denied in-patient treatment because their BMI was considered too high for an eating disorder.”

Why this memoir matters

Where “SLIP” truly shines is in its unfiltered account of Tarpley’s own state of being at the most difficult points of her disorder, drawing from memory, medical records and journal entries. She gives readers free rein inside her head—something many, if not most, parents of loved ones with eating disorders rarely get.

“I was navigating a debilitating duality: a hidden desire to get better and a fear of showing any sign of improvement. I worried that if I ate, people would think I was fully recovered: She can eat! Then: Let’s see what else she will eat! A hamburger? A slice of pizza? Ice cream? She’s better now! In my mind, the path to recovery was not a road but, rather, a tightrope stretched across a dark abyss. Everything about it seemed terrifying. I worried that if I walked across it and got better, I would lose the ecosystem of care that came with sickness.”

As we follow Tarpley through her recovery and the inevitable slips along the way, her eating disorder emerges as an unwanted but enduring presence, rising and receding through career milestones, falling in love, marriage, and motherhood. Though its grip loosens, it never fully disappears. Ultimately, she finds a kind of peace with its coexistence.

A caregiver’s takeaway

“SLIP”’s strength lies in its storytelling—both in Tarpley’s personal journey and in the voices of the dozens of sufferers, clinicians, and researchers she weaves in. What she offers is a more nuanced view of eating disorders and a clear-eyed look at what it means to recover in a world obsessed with thinness and fatphobia. Yet it never veers too far into preaching or judging. It overwhelmingly feels grounded in compassion—and hope.

“Recovery, I learned, is not a return to who you once were so much as a retrieval of all you lost while you were sick: pleasure, possibility, some semblance of peace. It requires a ruthless commitment to hard work. It’s an accumulation of slow steps, with an acceptance that some steps will lead to slips. And it’s a promise that you’ll be honest about the slips, knowing they are an inevitable part of progress. You can’t slip, after all, if you’re standing still. As you move forward, you may or may not reach full recovery, but you emerge as someone who can lead a fuller life.”

As someone who has served as a caregiver to two loved ones with anorexia, “Slip” was both resonant and perspective-shifting.

It challenged my own beliefs about what it means to be fully recovered from anorexia. By failing to make space for the messy middle, with its ups, downs, and inevitable slips, we risk doing a disservice to our loved ones. We create unrealistic expectations for recovery, ones rooted in absolutes and perfectionism, the very traits that often fuel eating disorders in the first place.

While “SLIP” is deeply personal, Tarpley’s inclusion of so many other voices offers a broader, more inclusive view of recovery, one that feels hopeful and accessible, even when full recovery often feels elusive. By illuminating the reality of the “messy middle,” she invites us to rethink what healing can look like.

💬 I’d love to hear from you.

Have you ever found yourself in the middle—between struggle and recovery, grief and growth? How has your understanding of healing evolved, either through your own experience or while supporting someone else? Whether you’re navigating the quiet work of recovery or rethinking what “better” looks like, I’d love to hear what that looks like for you.

Kristi, thank you for this beautiful review. I'm so glad that SLIP resonated with you and that you found it to be an honest and inclusive look at the recovery process. I'm beyond grateful that you took the time to read the book and write this review. I hope your readers will check out the book and that they'll find it helpful.

I am looking forward to reading the book. I used to be so defensive when people asked about our daughter's recovery, because I was so desperate to reach an endpoint. These days, I am more relaxed (it is easier, she is well), but I am not sure I believe there is an endpoint for anyone. We are all constantly experiencing life, and based on that experience, we get to change things or not. I am interested to see if the book changes my view.